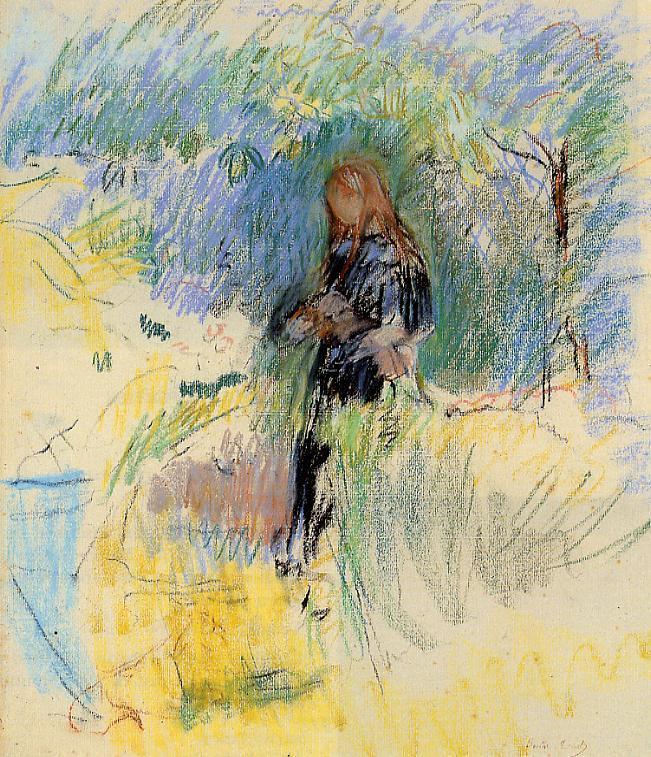

Berthe Morisot, Pastel on Paper, 1892

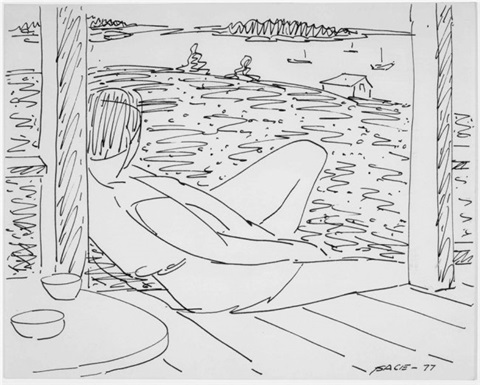

Berthe Morisot, Pastel on Paper, 1892 Stephen Pace, Ink on Paper, 1979

Stephen Pace, Ink on Paper, 1979 Dorothy Eisner, Oil on Canvas, n.d.

Dorothy Eisner, Oil on Canvas, n.d.

It may be that today the pleasure in painting the clothed figure in the landscape involves the artist’s unification of two distinct and autonomous genres of painting; figure and landscape. Their individuality was the result of a slow evolution. For example, even though painters like Rembrandt and Poussin made landscape the subject of sketches and drawings, historically landscape played a subordinate role to the figure, appearing as counterpoint in religious, political and history painting. It took centuries for landscape as an entirely singular subject to emerge. In fact, modern landscape only came into its own during the first half of the 19th century with Corot, the Barbizon School and then the Impressionists.

On the other hand, figure painting enjoys a much longer history than landscape, extending perhaps as far back in time as the Stone Age. Like siblings, these separate genres of painting have intertwined traits, sharing attributes and characteristics. At the same time each has endeavored to be independent and to be regarded in its own terms. Painting the clothed figure in landscape today mirrors and extends that process. In other words, reconciling the defining qualities of these two painting genres is in itself a subject of painting.

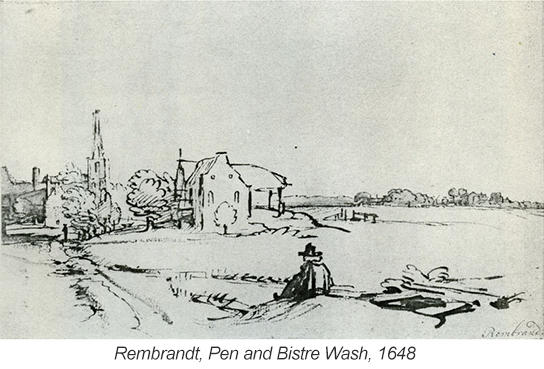

Generally speaking, a particular kind of pictorial space is associated with the separate disciplines of figure and landscape painting. One reason has to do with scale – the relative size or presence of the figure or the landscape in the picture field. In this sense scale also refers to the narrative importance that either the figure or landscape holds in the painting. A Rembrandt drawing illustrates this idea.

Formally the drawing is defined by breadth of space and size of forms; but importantly there is a narrative not unlike that of some Chinese landscape painting created by the juxtaposition of human scale and the surrounding landscape. Another way to describe this issue of proportion is to ask how one creates a vibrant equilibrium between the two subjects of figure and landscape and what the weighting of those subjects in the painting is.

Formally the drawing is defined by breadth of space and size of forms; but importantly there is a narrative not unlike that of some Chinese landscape painting created by the juxtaposition of human scale and the surrounding landscape. Another way to describe this issue of proportion is to ask how one creates a vibrant equilibrium between the two subjects of figure and landscape and what the weighting of those subjects in the painting is.

The clothed figure in landscape is far different in psychological resonance than the nude; the nude in landscape almost certainly creates a notable narrative juxtaposition. In contrast the clothed figure offers an opportunity to celebrate the every-day appearance of a figure in a scene. If that clothed figure is present in the landscape naturally, that is if it is simply being in the landscape, absent of an overt storyline of its own, we can see the figure as a commonplace cohabitant with its surroundings. Both visually and narratively the space offered by the figure and by the landscape can become a new fusion of form and color when expressed through the painter’s unique intellect and sensibility.

-Lon Clark, SFSS Dean

Richard Diebenkorn, Oil on canvas, 1957

Richard Diebenkorn, Oil on canvas, 1957

Charles Cajori, Seaside, oil on canvas, 2006

Charles Cajori, Seaside, oil on canvas, 2006

Georges Seurat, Seated Woman, Conté on paper, 1881

Georges Seurat, Seated Woman, Conté on paper, 1881